Some of you may be familiar with the Great Wall of China, a serpentine structure that displays the human tendency to segregate ourselves from people we don’t like at its most profound. We recently saw the return of YinYang Music Festival, a 2000 capacity three-day electronic offering featuring a wide range of local and international talents.

The organizers have done an amazing job developing it this far, from a purely practical standpoint (as we all know how difficult it is to push anything through in Beijing these days). But despite the encouraging signs of growth here, after watching the wrap videos and hearing the stories from attendees to this 2015 edition, there is a feeling among some that the (growing?) phenomena of turning historical relics into party sites is a bit much. In this article we’ll dig a little deeper to understand this sentiment.

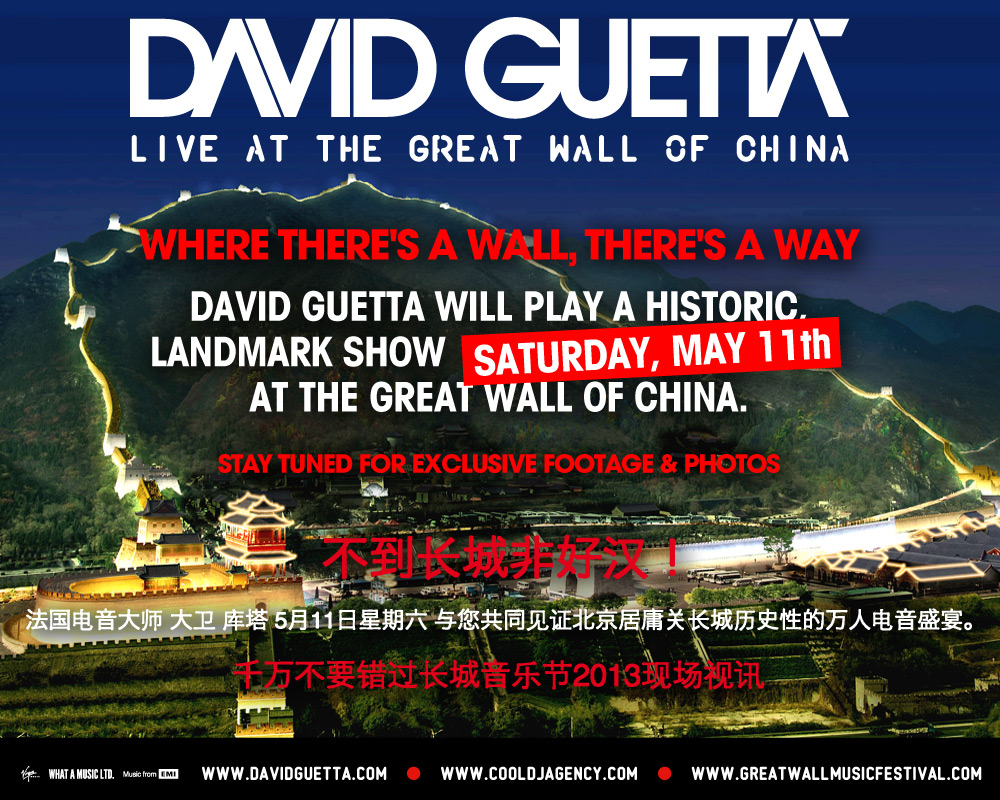

Firstly let’s make clear that we are talking broadly about the idea of hosting events on places of historical and cultural significance, rather than specifically targeting YinYang. Though Great Wall Music Festival 2013 was perhaps a watershed moment for many, with David Guetta’s appearance combined with the location really putting the fest on the international radar, in actual fact events have been taking place there since the late 90’s (they were actually banned in 2005). These early events established the model for a sort of turbo-charged location-branding exercise – go to Beijing, see the sites, and go on a rager while you’re at it.

The Great Wall wasn’t the first attraction to play host to an EDM bonanza. Let’s get some perspective on what’s going on elsewhere:

Entering its third year this year, Electric Castle is the largest music festival in Romania and it’s the first Romanian festival to take electronic dance music and live concert sounds to a castle’s domain, according to the festival’s PR. 2015 features 6 stages and over 150 artists.

The castle itself – Bánffy Castle, completed in 1890 – was declared a historic monument, and was recently renovated under the patronage of the Prince of Wales. Of course we must keep in mind that historically this was a privately owned property.

Organized by SEHER, SABF takes place in the ruins of Purana Qila (a.k.a. the Old Fort) in the heart of Delhi over 3 days. The event features music from the 9 SAARC nations, and is presented by the Indian Council for Cultural Relations (ICCR) in collaboration with the Ministry of External Affairs. So in this case we have a government-sanctioned use of a cultural relic.

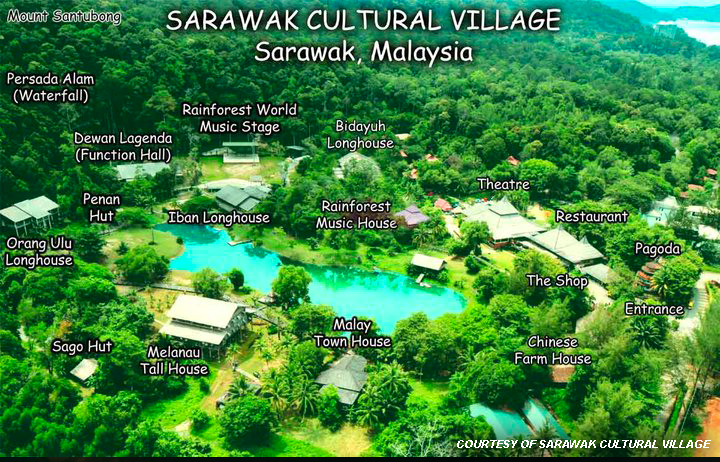

Rainforest World Music Festival

As you can see by the very striking image below, some festival organizers now seem to be plundering rainforests to host their events. This one takes place on Borneo and features not just music, but workshops, ethno-musical lectures and jam sessions.

The festival site borders the Kuching Wetland Areas – a RAMSAR site. For those who don’t know, the RAMSAR Convention is an international treaty for the conservation and sustainable utilization of wetlands. It’s hard to imagine the full extent of the impact of a music festival on a protected area, but we’d guess the noise would rattle a few cages in the best of cases. The festival is organized by the Sarawak Tourism Board.

Yanni @ The Taj Mahal

We couldn’t miss an opportunity like this…

So we have a mix of event properties here, some private, some run by the state. This distinction complicates the argument that is about to be put forward, as some may feel a government-owned or endorsed body represents the needs of the people, and should therefore be left to make use of national treasures in whichever way it may deem fit. But private (particularly profit-making) events are another matter, and probably require greater scrutiny.

Leave the Great Wall Alone?

Taken together, the organizers of these events probably have the best of intentions. They probably do everything in their power to guarantee the safety of people and preservation of the site and surrounding environment. They probably increase the profile of their locations of choice, benefiting the peripheral economy and welfare of locals. But we know what happens at festivals, don’t we? Raging tourists “embracing the moment”, fluorescent paints on body parts that should never see the light of day, and that one guy in a shirt who can’t follow a four to the floor beat aside, there will always be some element of damage and deterioration in even the most meticulously organized of events.

Returning to the Great Wall, many have already criticized the lack of preservation that has resulted in the desolation of large parts of the structure.

“The Great Wall of China, another Unesco site, is facing similar pressures. Entire sections have been rebuilt in a Disneyfied incarnation of the original, while others have been damaged by environmental erosion or dismantled by locals to build their homes. According to a recent analysis by the Chinese Association of Cultural Relics, a third of the wall has now disappeared.”

Against the backdrop of this reality, it is fairly reasonable for some to bemoan the presence of a music festival on a protected site or area. We spoke to a friend who attended the festival for an insider’s view on what actually went down at YinYang:

The site featured beautiful old stones that formed the structure of the main stage and camping sites, complementing the mountains that stretched as far as the eyes could see. It seemed at first the perfect spot for a good festival.

There were three main stages during YinYang, two main ones that weren’t held on the wall itself, but where a view of the Great Wall was still visible. The third small stage was held on the Wall itself, but the sight of people sleeping on the floor from exhaustion and the hundreds of cigarette butts and beer cans made it seem like something wasn’t right, it made you feel almost guilty being there. Moreover, the fact that it was held on the Great Wall meant hundreds of policemen were keeping a strict eye on everyone, even to the extent of stopping the music for a good 20 minutes on the festival’s opening night. We all love festivals and a festival in a beautiful site becomes a great Festival, but perhaps keeping two stages offering a view of the mountains and the Great wall could have been far more than enough.

The world’s best festivals are great because they provide an escape, an isolated place where craziness can take place with little consequence on others. There is a risk – and we’ll leave it for you to decide the extent of this risk – that the trend of curating party experiences on/in/around protected natural locations and heritage properties is picking up as economies become increasingly squeezed, and the fallout will be an increase in the use of protected sites for activities that will accelerate their deterioration, in any number of ways.

Beatport news staff claim “Partying at UNESCO World Heritage sites is pretty tight.” If it’s too late to reverse the trend, at the very least let’s be responsible and acknowledge that in many cases we are basically dancing on locations where sacraments were made, where people died, and where the essence of a given culture is concretized. These locations can’t be replaced.