by Will Griffiths with Archie Hamilton. More from Will over at www.livechinamusic.com

When COVID-19 hit China officially on January 24th, the whole country – starting with Wuhan – went on complete lockdown. Live music globally was among the first industries to be completely shut down and in most places, it will be the last to reopen. Here in China, some cities started preparing for reopening at the end of March, even though in reality officially sanctioned gigs didn’t emerge until the end of May. After a month of finding collective feet again, we were up to fullish speed by the end of June (with restrictions of course – no international artists and only in sub-500 capacity venues).

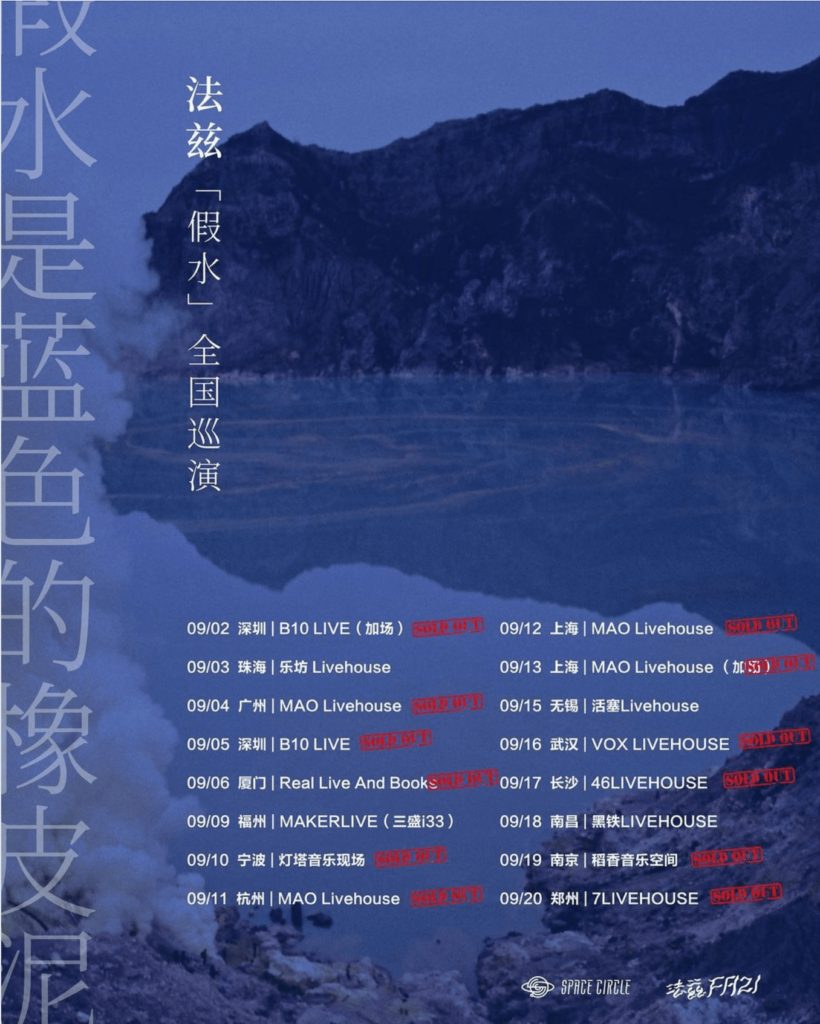

Since July, it’s been one tour after another; and more recently a re-emergence of festivals across the country. For the most part, everything has gone smoothly and most shows have sold out immediately, showing that there is indeed pent up demand after the lockdown. Bands that were already attracting attention last year have seen shows post-COVID sell out immediately with organizers scrambling to put on second nights. Seasoned acts that have worked the indie circuit for more than a decade are excited to see their hard work pay off. As always, the good is tempered by the bad – alongside the rebound demand is (an inevitable) sharp rise in prices. Tours now seem to have a base price of 100RMB while lineups with two to three bands can work their way up to 200RMB+. Hiperson’s upcoming tour is priced at 130RMB (a shade under US$20) in advance, with enough demand to add a separate afternoon show in some cities. Just last weekend, Modern Sky Lab in Shanghai hosted three relatively new bands (Wasted Laika, MoonBand, and Endless White) with tickets at 200RMB. The show sold out.

出海部 Wonder Sea – Guangzhou sold out show

A year ago, you would need a foreign act on the bill to push past the 200RMB mark for alterative artists, but now promoters seem confident in capitalizing on a nascent demand for local acts, a growing audience starting to see going to a gig in the same light as going to the club or KTV. Festival prices are also up and seem to have settled in the 300-500RMB per day range (for reference, this year’s Rye Music Festivals is 330RMB (over US$45) in advance).

So what gives?! Are venues, promoters, and labels evolving or looking to cash out. A little bit from column A and a little bit from column B?

One of the interesting wrinkles to these developments is the post-COVID reality that most of the music venues are living. Namely, audience capacity restrictions (which range from 70% to the extremely challenging limitation of just 30%) are forcing tickets prices vertically skyward to make up for the missing buyers. This also leads to a strange side-effect: shows ‘selling out’ quicker than ever, something promoters are using to add hype to their shows.

We wouldn’t be surprised to see prices stay at this new bar even as restrictions loosen up. The customers have spoken (for the time being).

Finally, to the big news of the pandemic, the latest in a string of music based reality TV programmes. The first season of The Big Band proved that the rock scene does indeed have mass appeal – it just needed a little nudge. Season 2 couldn’t have come at a more opportune time. Every band in China seems to be keen on the promotional push and many are taking advantage (just look at the increase in Weibo fans from before the show began to now) — from tours conveniently starting in the midst of the show to a slew of songs releases. These tours are selling out like crazy.

But it’s not only bands on the Big Band that are strategically capitalizing on their newfound fame. Indie favorites such as Hiperson, and Wonder Sea 出海部 have sold out wide ranging tours around China – the former, in what seems like a valiant grassroots effort by the band utilizing their artistic clout to their advantage, the more like a effectively coordinated effort cooked up by the band’s label (although please check out Wonder Sea’s new album – it’s damn good).

As always, it’s important to also look at the other end of the spectrum. There is an ever widening gap between trending bands and local acts who haven’t broke through yet or are just cutting their teeth. Venues in Shanghai bounce from a sold out show one evening to a show with only 20 presale tickets sold. Audiences aren’t willing to take risks anymore. Venue fees and licensing costs are keeping many bands without representation at bay —— leaving both venues and bands dissatisfied. How does one continue to feed the next generation of artists? Free gigs are one way to circumvent some costs but for venues it’s still a tough financial pill to swallow. Whatever the case, the current environment will likely have an inverse effect on the scene and may likely push a lot more of it underground (for better or worse). Venues may be happy at the moment with the sold out tours and the push that endeavors like The Big Band are providing, but they also know that it’s not sustainable and isn’t fostering any kind of long-term growth.

The Big Band is unarguably profiting from 15 years of other people’s investment in the artists they feature: from loss making festivals, to album releases that had no way of making a return, to livehouses that survived on the smell of an oily rag. The passion and dedication of venue owners, promoters, artist managers and the bands themselves is now being radically monetized inside a narrow band of musicians and an even narrower band of industry giants (Taihe and Modern Sky represent the vast majority of these artists), and as is most often the case, this is being done with short term profits riding roughshod over longer term success and maturity.

Will this last? We can look to the Rap of China (another iQiyi production) for some kind of benchmark. Season 1 was a bolt out of the blue, a huge swell of realization, not only that hip-hop existed in China, but that some of it was pretty good. The Rap of China Season 2 and all the myriad copycat shows have been underwhelming in comparison, but hip-hop and its artists have benefitted magnificently. Hip-Hop festivals (pre-COVID), were drawing unprecedented audiences around the country, rappers are earning huge money (and audiences), and some have gone global. Since the Rap of China Season 1, hip-hop has moved aside to make way for the latest reflection of the zeitgeist, but this short term success has left a longer term residue. Hip-hop might not be quite so mainstream in 2020, but it is massive and growing in the underground.

The indie music that forms the backbone of the Big Band has much deeper roots and broader appeal than hip-hop did at the same stage, although it is geared to an older demographic. In the months and years to come, we might see some artists genuinely jump from alternative to enduring popstars during this transition, which would be the first time in China’s developing music industry that this has occurred.

Whatever happens, China’s domestic music scene now has genres and options and that is exciting to bear witness to.