[This is an annual look at the state of the Chinese music business from an insider’s perspective. Click through for our essays on 2016, 2017 and 2018]

Short answer: nope.

Long answer: the Year of the Dog was a year of profound mismatch.

A year where expectations did not match the reality (and sometimes didn’t matter), where hype did not match the facts on the ground, and where investment and media attention did not match what really mattered.

A year where the strong emphasis on creativity under the government of Hu and Wen (2002-2012) has completely and utterly disappeared from view.

We’ve written before about navigating the multiple, sometimes paradoxical, scalesat which one needs to see the Chinese music industry, so as always: let’s look at the top-level first.

Tencent made global headlines with its massive $1.1 Billion IPO, but its filing suggests that the future of the company lies away from music delivery itself – in entertainment (live streamed karaoke and virtual gifting made up a large part of revenue and profit), events, brand partnerships and licensing. Only 4% of its users pay for access to streaming music, and with heavy competition from Netease and (less so) Alibaba-backed Xiami & Baidu Music, this is unlikely to see significant growth.

Tencent & Netease are still chasing exclusive distribution and licensing deals(Xiami seems to have dropped out of the running here) parceling up music databases between their respective proprietary platforms. For the omnivorous music listener, it’s quite common to hedge bets between all three – QQ Music, Xiami and Netease Music – in order to have access to all the songs you love.

The tendency to “monopolize” gives the Chinese music industry some of its tireless energy, but this moat-building is also exhausting for the end user who must commit absolutely to one ecosystem of apps at the expense of others. As the alarming rise and fall of Ofo bikes shows in an adjacent industry, this approach favors short term gains over long term resilience, a nuance we’ve alluded to many times before.

Elsewhere, a similar mindset is at work with Taihe Music Group, rising through the ranks to become one of China’s biggest players in the live and “indie” space and rivaling Modern Sky who spent most of 2018 expanding abroad. Taihe’s ‘Indie Works’ initiative has roped in pretty much every label and underground outfit across China including (the acquisition of) Beijing stalwart Maybe Mars (clearly they read our 2016 essay in praise of Chinese labels). When everything is an arm of a giant corporation – what really is the indie scene anymore?

That “indie” scene had a mixed 2018. Cities in the south of China continued to produce exciting new sounds (especially the FunctionLab crew in Hangzhou, whatever they’re drinking/smoking in Chengdu’s Sichuan Conservatory of Music, and Guangzhou’s Qiii Snacks and its affiliates). Up in the northern wastes, long running Beijing venue Yugong Yishan shut its doors after 13 years in the game. They plan to re-open in a new location, but have shifted their attention momentarily to electronic with new venue collaboration Zhaodai. Venue owners and promoters are predicting a gloomy 2019, with some important anniversaries sprinkled around the year that promise frequent clampdowns on performances.

On the festival front, we can confidently say that EDM has plateaued and is on the decline. An oversaturated scene of foreign imports (Creamfields, Ultra, EDC) played to ever diminishing returns as they struggle to differentiate themselves from a crowded field. Some festivals, like Dutch import Daydream, are moving towards a “hybrid” model – combining live acts and underground bands with the sound-and-light DJ spectacles. One representative incident involved a “fake-but-eventually-not” China edition of the Djakarta Warehouse Project booking and hip-hop diva Nicki Minaj, who eventually refused to take stage after witnessing a gigantic mismatch between what was promised and the reality of the festival. Despite a drop from the peak, the massive hype around EDM over these last few years has seen a genuine love emerge for the genre and it is now the most streamed non-pop category on the Chinese services. That same phenomenon can be seen more recently for Chinese hip-hop.

The festival market more broadly has suffered from rising costs and stagnant demand. The 2013-17 boom in large outdoor music events and an overall upward pressure on wages has pushed up the prices of everything from artists to stages, security to temporary tent supplies. Allied to a broad contraction in investment funding across all industries at the end of 2018 (the festival sector suffered, but not more than any other), many festivals with ill-defined offerings and poor execution have died. The hope now is that with less “underwhelming” competitors diluting the audience, good brands will survive and thrive.

Then there’s TikTok. The hotly tipped behemoth has been aggressive in its push to dominate the cultural landscape of music in China, even partnering with the CCTV Spring Gala. But that partnership illustrates the mismatch in the app’s fundamentals: its chaotic energy has been clipped by a series of new, harsh content bans, and the only way forward is to actively court the state and its sanctioned media institutions, a move that goes against everything its user base desires.

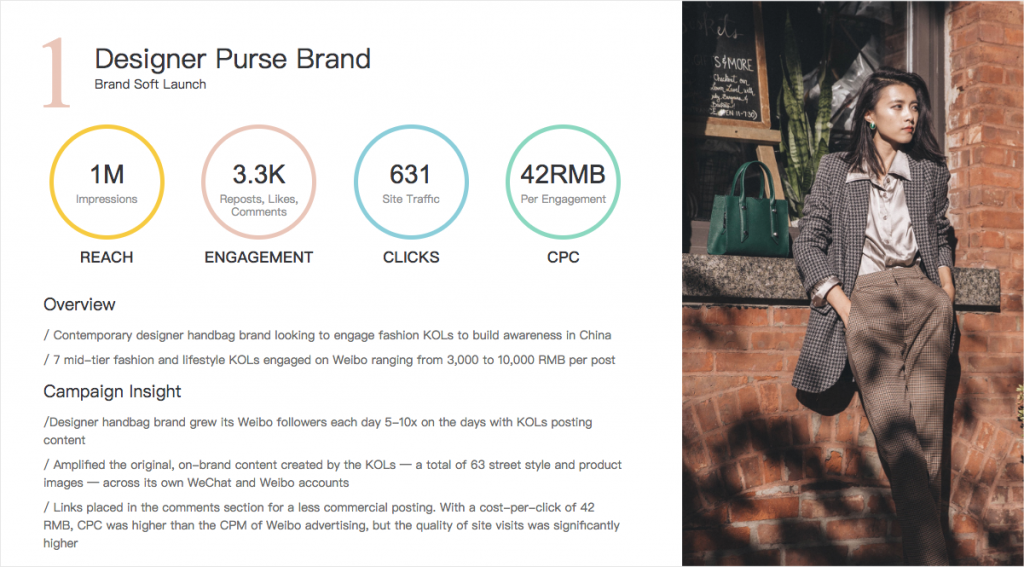

Finally, 2018 was the year of data, both in the music industry and across others. A&R is now the job of a data scientist, as promoters and label bosses scour streaming numbers and social media engagement and use both to hone their decision making. The rise of influencers and KOL’s has pushed its way front and centre in music as well, and begs the question, “is it about the music or the celebrity?”. The money on offer from partnerships (as well as the virtuous circle of “more likes = more likes”) has led to a global distrust of data. This is particularly prevalent in China, where you can literally buy views // listens // likes for a few jiao on Taobao.

At this point, it’s worth recapping some of the dominant themes of the year:

- There’s a fundamental mismatch between business moves at China’s biggest music companies and what’s “good” for the health and resilience of the sector. A “war” mentality, a ruthless urge to monopolize and corner exclusives creates walled gardens that ultimately alienate end users.

- There’s a mismatch between demand and supply of live music. Too much EDM is chasing diminishing audiences, while a growing audience for alternative sounds is meeting a supply gap, filled partially by industrious Taiwan bands from across the strait and a mega influx of Japanese bands of all shapes and sizes. More foreign acts are playing China than ever before, but rising costs (including venues, visas, hotels and taxes) means ticket prices have gone through the roof while a consumption downgrade has hit a slowing economy,creating a mismatch with what punters are willing (and able) to pay and what promoters increasingly need to charge.

- There’s a mismatch between hype and reality. Season 2 of The Rap of China was defanged and dethroned as the country’s hottest cultural product, with finalists (despite giant marketing campaigns) playing to half-empty livehouses on their victory lap tours.

- There’s a mismatch between the top-down and the bottom-up. A ruthless standardization and crackdown on the wilder fringes of society has made the music scene, for lack of a better word, a little bit boring. This is not to say that exciting work isn’t being produced (a lot is!), but the pipeline to greater recognition and professionalism has been broken. Many underground acts are forced to stay solidly underground, with any visibility now needing official approval and sanction.

- This is only marginally related, but both QQ and Netease’s year-end charts are utterly dominated by Japanese music – which remains the dominant source of pop-culture cool among Chinese youth. So much so that even the powers-that-be are using anime, such as this new animated series on Karl Marx, to push their own narrative.

So where does all this leave us?

As we’ve pointed out before, what the scene needs is already there – it’s just not being prioritized. The industry is less interesting because bottom-up diversity is being eroded by a top-down standardization. The club scene – where much of the new and interesting is gestated and nurtured – is in constant fear of censure, both from a content promotion perspective and then from an audience and local regulation perspective. It seems obvious that the controlling class (at least in the current climate) is not truly committed to the continued development of creative industries. It seems unreasonable to expect a system that has been so successful over the last 40 years to morph completely, but some balance is necessary to engage and harness the youth and keep the forward momentum. There is no balance at present.

China may well believe it has succeeded in becoming a nation of innovators and creators – certainly the tech sector has done amazingly well at reinventing itself after years of being viewed as copycat only – but are these successes only a result of the supportive policies from the end of the 90’s to the mid-10’s? Since then, a rejuvenation of the SOE sector and a vice-like grip on an increasingly localized intranet has created a fear of self-expression where once there was a sense of adventure. The pendulum needs to swing back soon to arrest the slide, something that seems unlikely to happen given the current ideology.

Perhaps the rise of the 88Rising brand in 2016 and ‘17, continued and elevated international successes for an increasing number of Chinese artists and the appetite for “made in Asia” music abroad shows us a way forward. There is no shortage of fascinating ideas and peerless talent here in China. There’s plenty of capital and money too – all it needs is a little restraint, and a little bit more long-term planning. It needs an understanding that music can be medicine for these wounded and divided times.

As an industry, we need to push creativity, art and ideas out into the open…rather than lock them in. Let’s hope the Year of the Pig starts to move us back in that direction.