Ah, spring.

The frost is melting, the sun is shining, and all of the fandoms are out in full force again.

It truly is the season of fan excess here in China at the moment.

This week, over-excited fans of an unnamed pop idol ended up smashing fixtures at Shanghai’s Hongqiao Airport, even forcing national mouthpiece The People’s Daily to respond with characteristic moral tut-tutting.

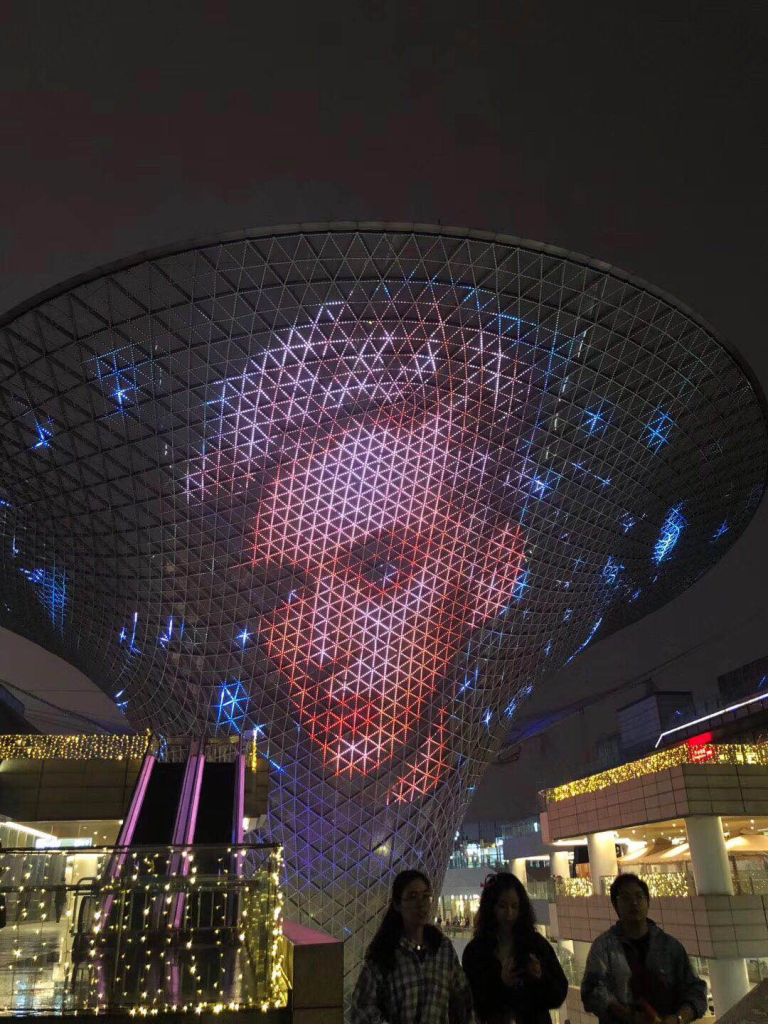

In less-destructive but equally attention-grabbing gestures, a coven of Troye Sivan fans bought out the entire outer facade of the city’s Mercedes Arena, prime ad-space, to project a slideshow of images of the young pop-star.

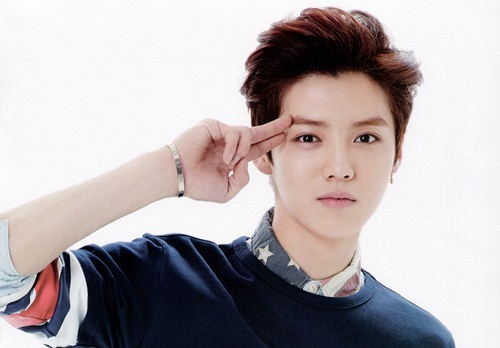

These incidents cap off a year of fan excess, from proven account fraud to boost Kris Wu to the top of the iTunes charts, to brigading BiliBili to remove videos of idol Cai Xukun playing basketball badly. Buying ad time at New York’s Times Square for “birthday greetings” has become de riguer for Chinese fans of idol stars, from TFBoys to BTS.

It’s truly spring time for the fan economy in China, and we’re not the only ones flexing for seasonal metaphors.

“In the past, China’s idol market was like a desert, with the rare oasis here and there. But thanks to the growing influence of South Korea’s pop culture in China, the soil has become fertile here this year, and everyone has started planting crops.”

A report by the securities firm Zhongtai predicts that the fan economy and idol industry could reach a staggering CNY 100 billion by 2020. But the issue here can be gleaned by the language used: “economy”, “industry”.

The Chinese idol business is a wholesale adoption of the South Korean model, complete with brutal training regimes and oligarchic umbrella companies for management and performances.

Add to this the pile-on “move fast and break things” mentality that drives Chinese industry bubbles, and you get a fragile boom. In the words of Sixth Tone, the fan economy “will not save China’s music industry.”

What we have, then, is a system similar to the early days of livestreaming in China (brilliantly captured in Hao Wu’s People’s Republic of Desire). A model where both the fans seeking genuine connection and the idols seeking fame and recognition are subject to the whims of investor interest, and eventually, state intervention on moral grounds.

Within the reality TV world, 2018 was called “the first year of the idols’ reign.” One year in, and not much seems to indicate that it’s going to be a long and peaceful rule.